|

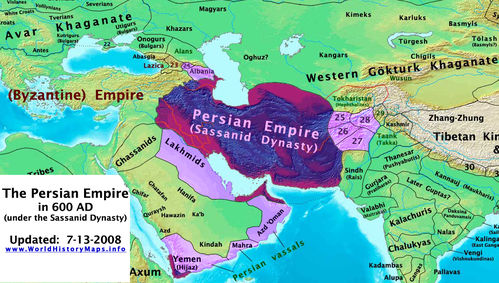

| The Roman - Persian frontier. |

Roman – Persian War of 572–591

The wars between the Roman Empire and Sassanid Persia had gone on and on for centuries. Each side looking to gain territory or military advantage over the other. The latest war was triggered by pro-Roman revolts in areas of the Caucasus under Persian hegemony, although other events contributed to its outbreak.

The politics and brushfire mini-wars of the period can easily make you dizzy. The connections and interconnections and political-military layers are no different than the world today.

You had the Eastern Roman Empire attempting, and failing, to make a military alliance with Turkish tribes in Central Asia against Persia. The Roman Empire and the Persian kingdom were in very similar circumstances. The Romans were placed between the Avars in the West and the Persians, just as the Persians were placed between the Turks (on the north) and the Romans.

|

| Historical re-enactment of a Sassanid-era Persian Cataphract. Light to heavy armored cavalry were used by the Persians. |

The Romans also backed a pro-Roman faction in a takeover of Yemen. The Persians in turn backed their allies in restoring a Persian client state in Yemen. Both sides had their client Arab tribes battle each other on the frontier.

The Christians in Anatolia and the Caucasus region were in a constant state of actual or intermittent rebellion. As the Christian population could not remain happy under Persian domination, they appealed to the Emperor of the Romans in the name of their common religion. In 570 the Romans made a secret agreement to support an Armenian rebellion against the Sassanids, which began in 571, accompanied by another revolt in Iberia.

Any one of the causes mentioned might have been insufficient to produce a rupture, but all together were irresistible, and accordingly, when the time came for paying the stipulated peace treaty annuity, Emperor Justin II refused (572). The war which ensued lasted for twenty years; and its conclusion was due to the outbreak of a civil war in Persia.

The War Begins

Early in 572 the Armenians under Vardan Mamikonian defeated the Persian governor of Armenia and captured his headquarters at Dvin; the Persians soon retook the city but shortly afterwards it was captured again by combined Armenian and Roman forces and direct hostilities between Romans and Persians began.

By joining the Iberians, Lazi and Romans in a coalition of the region's Christian peoples, the Armenians dramatically shifted the balance of power in the Caucasus, helping Roman forces to carry the war deeper into Persian territory than had previously been possible on this front.

The Fall of Dara

In Roman Mesopotamia the war began disastrously. After a victory at Sargathon in 573 they laid siege to the fortress of Nisibis and were apparently on the point of capturing this, the chief bulwark of the Persian frontier defenses, when the abrupt dismissal of their general Marcianus led to a disorderly retreat.

Persian forces under Shah Khosrau I (531-579) swiftly counter-attacked and encircled Dara. Khosrau besieged it, using against its walls the engines which the Romans had left behind them at Nisibis. But it was not easily taken, and the Persians almost despaired. Finally, over-confidence produced remissness in the garrison, and after a siege of six months the city passed into the hands of the Persians. Khosrau now held the two great fortresses of eastern Mesopotamia, Nisibis and Dara.

|

| Minted Coin of Persian Shah Khosrau I. |

At this juncture the Persians and their Arab allies invaded Syria and laid it waste as far as Antioch.

The invasion of Syria took place under the leadership of Adarmahan, and the country, as has been said, was devastated up to the walls of Antioch. The city of Apamea was committed to the flames. Syria seems to have been entirely undefended; for thirty years the inhabitants had been exempt from hostile attacks, and had consequently become so unaccustomed to the sights of war that they were unable to take measures for their own defense. The captives who were led away to Persia are said to have numbered in the tens of thousands.

To make matters worse, in 572 the Emperor Justin II (565–578) had ordered the assassination of his Arab ally the Ghassanid king al-Mundhir III. Needless to say, the formerly pro-Roman tribe did nothing to help the Empire during this phase of the Persian invasion.

The Empire needed to buy time to regroup. In 574 the Romans agreed to pay 45,000 nomismata for a one-year truce, and later in the year extended this to five years, secured by an annual payment of 30,000 nomismata. These truces applied only to the Mesopotamian front and elsewhere the war went on.

|

| Eastern Roman Empire infantry. |

In 575 the Romans managed to settle their differences with the Ghassanids; this renewal of their alliance at once bore dramatic fruit as the Ghassanids sacked the Lakhmid capital at Hira. In the same year Roman forces took advantage of the favorable situation in the Caucasus to campaign in Caucasian Albania.

In 576 Khosrau set out on what was to be his last campaign and one of his most ambitious, staging a long-range strike through the Caucasus into Anatolia, where Persian armies had not been since the time of Shapur I (241-272). His attempts to attack Theodosiopolis and Caesarea were thwarted, but he managed to sack and burn Sebasteia before withdrawing.

Justinian, the son of Germanus, was appointed Magister militum (Latin for "Master of the Soldiers") and marched his troops to Armenia (576) to meet the Shah in battle.

The Shah found himself in serious difficulties in a hostile and mountainous country, and apparently not supported in the rear. Khosrau began to retreat. But he was not allowed by Justinian to depart with impunity; the Romans pressed on, and the Persians were forced to fight against their will.

The battle was fought somewhere between Sebaste and Melitene, probably in the valley of the river Melas, land its details are described or invented by a rhetorical historian. It resulted in a complete victory for Justinian. Khosrau was forced to flee from his camp to the mountains, and leave his tent furniture, with all the gold, the silver, and the pearls which an oriental monarch required even in his campaigns. The booty, it is said, was immense.

The routed Persians grumbled at their lord for conducting them into this hole in the mountains, and Khosrau with difficulty mollified their indignation by an appeal to his gray hairs. Then the Sassanid descended into the plain of Melitene and burned that city, which had no means of resisting his attack. In the meantime, it may be asked, how was the Roman army occupied? It would seem that there was nothing to prevent the Romans from following the defeated and demoralized Persians, and at least hindering the destruction of Melitene, if they did not annihilate the host. This loss of opportunity is ascribed by a contemporary to the envy and divisions that prevailed among the Roman officers.

After the conflagration of Melitene, Khosrau retired towards the Euphrates, but he received a letter from the Roman general, reproaching him for being guilty of an unkingly act in robbing and then running away like a thief. The great king consented to accept offer of battle, and awaited the arrival of the Romans. The adversaries faced one another until the hour of noon; then three Romans rode forth, three times successively, close to the Persian ranks, but no Persian moved to answer the challenge. At length Khosrau sent a message to the Roman generals that there could be "no battle today," and took advantage of the fall of night to flee to the river. The Romans pursued and drove the fugitives into the waters of the Euphrates. More than half of the Persian army was drowned; the rest escaped to the mountains. It is said by Roman historians that Khosrau signalized these reverses by passing a law that no Persian king should ever go forth to battle in person.

Sassanian Persian fortress in Derbent, Russia

The twenty-meter-high walls with thirty north-looking towers are believed to belong to the time of Khosrau I of Persia. The chronicler Movses Kagankatvatsi wrote about "the wondrous walls, for whose construction the Persian kings exhausted our country, recruiting architects and collecting building materials with a view of constructing a great edifice stretching between the Caucasus Mountains and the Great Eastern Sea." This Persian fortress is a good example of walled cities that both Roman and Persian armies would face in their endless border wars, sieges and invasions.

Thus the campaign of 576 was attended with good fortune for the Romans, notwithstanding the destruction of Sebaste and Melitene. Nor were the events to the west of the Euphrates the only successes. Roman troops penetrated into Babylonia, and came within a hundred miles of the royal capital; the 24 war elephants which they carried off were sent to Constantinople.

The Romans exploited Persian disarray by raiding deep into Albania and Azerbaijan, launching raids across the Caspian Sea against northern Iran, wintering in Persian territory and continuing their attacks into the summer of 577. Khosrau now sued for peace, but a victory in Armenia by his general Tamkhosrau over his recent nemesis Justinian stiffened his resolve and the war continued.

In 576 - 577, the Persian general Tamkhusro invaded Armenia, where he defeated the Byzantines under Justinian. Later, Tamkhusro and Adarmahan launched a major raid into the Byzantine province of Osroene. They threatened the town of Constantina, but withdrew when they received word of the approach of the Byzantine army under Justinian. Following these reversals, later in the same year, the Byzantine regent, Caesar Tiberius, appointed Maurice as Justinian's successor.

Mesopotamia and Stalemate

|

| A coin with Maurice in consular uniform. Maurice served as the Roman commander on the Persian front and went on to become Emperor. |

In 580 the pro-Roman Ghassanid Arabs scored yet another victory over the pro-Persian Lakhmids, while Roman raids again penetrated east of the Tigris. However, around this time the future Khosrau II was put in charge of the situation in Armenia, where he succeeded in convincing most of the rebel leaders to return to the Sassanid allegiance, although Iberia remained loyal to the Romans.

The following year, an ambitious campaign along the Euphrates by Roman forces under Maurice and Ghassanids under al-Mundhir III failed to make progress, while the Persians under Adarmahan mounted a devastating campaign in Mesopotamia.

To concentrate on the Persian front, the Emperor Tiberias purchased peace with the Balkan Avars for 80,000 aurei. Maurice became Emperor in 582 and continued the war as well as reforms in the Roman army. For example, Maurice re-introduced the Roman custom of entrenching the army camps.

During the mid-580s the war continued inconclusively through raids and counter-raids, punctuated by abortive peace talks; the one significant clash was a Roman victory at the Battle of Solachon in 586.

In 588 there was a mutiny by unpaid Roman troops who also had their rations reduced by 25%. Their new commander, Priscus, was wounded and fled. This seemed to offer the Sassanids a chance for a breakthrough, but the mutineers themselves repulsed the ensuing Persian offensive; after a subsequent defeat at Tsalkajur, the Romans won another victory at Martyropolis. During this year, a group of prisoners taken at the fall of Dara 15 years earlier reportedly escaped from their prison in Khuzestan and fought their way back to Roman territory.

A Civil War in Persia

In 589 the war was raging on all fronts in Central Asia, the Caucasus, the the Arabian desert frontiers.

In Central Asia the Persians were led by General Bahram Chobin who was chosen to lead an army against the Turkish tribes of the region. Bahram's 42,000 man army included 12,000 hand picked Savaran, Persia's elite soldiers. He successfully defeated a large Turkish army. Reportedly, the Turkish forces outnumbered his troops five to one. Relying on the discipline and superior training of his Persian Cataphract cavalry.

His army defeated the Turks and Hephthalites in April 588 and again in 589, capturing Balkh and Herat respectively. He then proceeded to cross the Oxus river and managed to repulse the Turkish invasion.

In the Caucasus, Roman and Iberian offensives were repulsed by the Persian general Bahram Chobin, who had recently been transferred from the Central Asian front. After suffering a minor defeat in battle on the river Araxes in Azerbaijan against the Romans, Shah Hormizd IV humiliated him, sending him women's clothing to wear.

Enraged at this humiliation, Bahram raised a revolt which soon gained the support of much of the Sassanid army. Alarmed by his advance, in 590 members of the Persian court overthrew and killed Hormizd, raising his son to the throne as Khosrau II (590–628). Bahram pressed on with his revolt regardless and the defeated Khosrau was soon forced to flee for safety to Roman territory, while Bahram took the throne as Bahram VI.

With support from the Emperor Maurice, Khosrau set out to regain the throne, winning the support of the main Persian army at Nisibis and returning Martyropolis to his Roman allies. Early in 591 an army sent by Bahram was defeated by Khosrau's supporters near Nisibis, and Ctesiphon was subsequently taken for Khosrau by Mahbodh.

Having restored Dara to Roman control, Khosrau and the magister militum of the East Narses led a combined army of Roman and Persian troops from Mesopotamia into Azerbaijan to confront Bahram, while a second Roman army under the magister militum of Armenia John Mystacon staged a pincer movement from the north. At the Battle of Blarathon near Ganzak, a combined allied army of Romans and Persians decisively defeated Bahram, restoring Khosrau II to power and bringing the war to an end.

Bahram fled to the Turks in Central Asia and settled in Ferghana. After some time he was murdered by the hired assassin sent by Khusrau II.

The Romans were left in a dominant position in their relations with Persia. The Persians handed over many Roman cities. The extent of effective Roman control in the Caucasus reached its zenith historically. Also, unlike previous truces and peace treaties, which had usually involved the Romans making monetary payments either for peace, for the return of occupied territories or as a contribution towards the defense of the Caucasus passes, no such payments were included on this occasion, marking a major shift in the balance of power. The Emperor Maurice was even in a position to overcome his predecessor's omissions in the Balkans by extensive campaigns.

A HISTORY OF THE LATER ROMAN EMPIRE, by J.B. Bury