|

| Illustration of the Black Death from the Toggenburg Bible (1411) |

The Great Pestilence (A.D. 542‑543)

Long before the famous Black Death of the Middle Ages, the Eastern Roman Empire was devastated by the plague. The massive deaths weakened the Empire and its economy.

History of the Later Roman Empire

by J. B. Bury

(1923)

Justinian had been fourteen years on the throne when the Empire

was visited by one of those immense but rare calamities in the presence of which

human beings could only succumb helpless and resourceless until the science of

the nineteenth century began to probe the causes and supply the means of

preventing and checking them.

.

The devastating plague, which began its course in

the summer of A.D. 542 and seems to have invaded and

ransacked nearly every corner of the Empire, was, if not more malignant, far

more destructive, through the vast range of its ravages, than the pestilences

which visited ancient Athens in the days of Pericles and London in the reign of

Charles II; and perhaps even than the plague which travelled from the East to

Rome in the reign of Marcus Aurelius. It probably caused as large a mortality in

the Empire as the Black Death of the fourteenth century in the same countries.

.

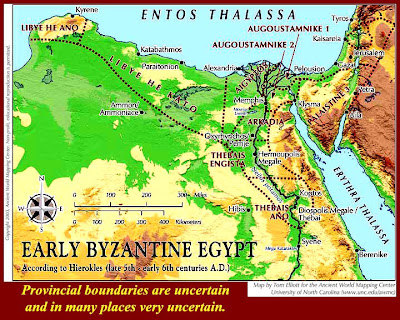

The infection first attacked Pelusium, on the borders of Egypt,

with deadly effect, and spread thence to Alexandria and throughout Egypt, and

northward to Palestine and Syria. In the following year it reached

Constantinople, in the middle of spring, and spread over

Asia Minor and through Mesopotamia into the kingdom of Persia. Travelling by

sea, whether from Africa or across the Adriatic, it invaded Italy and Sicily.

.

It was observed that the infection always started from the

coast and went up to the interior, and that those who survived it had become immune. The historian

Procopius, who witnessed its course at Constantinople, as Thucydides had studied

the plague at Athens, has detailed the nature and effects of the bubonic

disease, as it might be called, for the most striking feature was a swelling in

the groin or in the armpit, sometimes behind the ear or on the thighs.

.

Hallucinations occasionally preceded the attack. The victims were seized by a

sudden fever, which did not affect the colour of the skin nor make it as hot as

might be expected.

|

| The outbreak in Constantinople was thought to have been carried to the city by infected rats on grain boats arriving from Egypt. To feed its citizens, the city and outlying communities imported massive amounts of grain—mostly from Egypt. Grain ships may have been the original source of contagion, as the rat (and flea) population in Egypt thrived on feeding from the large granaries maintained by the government. The Byzantine historian Procopius first reported the epidemic in AD 541 from the port of Pelusium, near Suez in Egypt. |

|

| The Angel of Death comes. |

_______________________________________

The Historian Procopius Says -

"The fever was of such a languid sort from its commencement and up till

evening that neither to the sick themselves nor a physician who touched them

would it afford any suspicion of danger. . . . But on the same day in some

cases, in others on the following day, and in the rest not many days later a

bubonic swelling developed. . . . Up to this point everything went in about the

same way with all who had taken the disease. But from then on very marked

differences developed. . . . There ensued with some a deep coma, with others a

violent delirium, and in either case they suffered the characteristic symptoms

of the disease. For those who were under the spell of the coma forgot all those

who were familiar to them and seemed to be sleeping constantly. And if any one

cared for them, they would eat without waking, but some also were neglected and

these would die directly through lack of sustenance."

.

"But those who were seized

with delirium suffered from insomnia and were victims of a distorted

imagination; for they suspected that men were coming upon them to destroy them,

and they would become excited and rush off in flight, crying out at the top of

their voices. And those who were attending them were in a state of constant

exhaustion and had a most difficult time. . . . Neither the physicians nor other

persons were found to contract this malady through contact with the sick or with

the dead, for many who were constantly engaged either in burying or in attending

those in no way connected with them held out in the performance of this service

beyond all expectation. . . . [The patient] had great difficulty in the matter

of eating, for they could not easily take food. And many perished through lack

of any man to care for them, for they were either overcome with hunger, or threw

themselves from a height."

.

Procopius continues, "And in those cases where neither coma nor delirium came on, the bubonic

swelling became mortified and the sufferer, no longer able to endure the pain,

died. And we would suppose that in all cases the same thing would have been

true, but since they were not at all in their senses, some were quite unable to

feel the pain; for owing to the troubled condition of their minds they lost all

sense of feeling."

"Now some of the physicians who were at a loss because the symptoms were not

understood, supposing that the disease centred in the bubonic swellings, decided

to investigate the bodies of the dead. And upon opening some of the swellings

they found a strange sort of carbuncle [ἄνθραξ] that

had grown inside them."

"Death came in some cases immediately,

in others after many days; and with some the body broke out with black pustules

about as large as a lentil, and these did not survive even one day, but all

succumbed immediately. With many also a vomiting of blood ensued without visible

cause and straightway brought death. Moreover I am able to declare this, that

the most illustrious physicians predicted that many would die, who unexpectedly

escaped entirely from suffering shortly afterwards, and that they declared that

many would be saved who were destined to be carried off almost immediately.

. . . "

"While some were helped by bathing others were harmed in no less degree.

And of those who received no care many died, but others, contrary to reason,

were saved. And again, methods of treatment showed different results with

different patients. . . . And in the case of women who were pregnant death could

be certainly foreseen if they were taken with the disease. For some died through

miscarriage, but others perished immediately at the time of birth with the

infants they bore. However they say that three women survived though their

children perished, and that one woman died at the very time of child-birth but

that the child was born and survived."

.

"Now in those cases where the swelling rose to an unusual size and a discharge

of pus had set in, it came about that they escaped from the disease and

survived, for clearly the acute condition of the carbuncle had found relief in

this direction, and this proved to be in general an indication of returning

health. . . . And with some of them it came about that the thigh was withered,

in which case, though the swelling was there, it did not develop the least

suppuration. With others who survived the tongue did not remain unaffected, and

they lived on either lisping or speaking incoherently and with difficulty."

_____________________________________

This description shows that the

disease closely resembled in character the terrible oriental plague which

devastated Europe and parts of Asia in the fourteenth century. In the case of

the Black Death too the chief symptom was the pestboils, but the malady was

generally accompanied by inflammation of the lungs and the spitting of blood,

which Procopius does not mention.

.

In Constantinople the visitation lasted for four months

altogether, and during three of these the mortality was enormous. At first the

deaths were only a little above the usual number, but as the infection spread

5000 died daily, and when it was at its worst 10,000 or upward. This figures are

too vague to enable us to

conjecture how many of the population were swept away; but we may feel sceptical

when another writer who witnessed the plague assures us that the number of those

who died in the streets and public places exceeded 300,000.

If we could

trust the recorded statistics of the mortality in some of the large cities which

were stricken by the Black Death — in London, for instance, 100,000, in Venice

100,000, in Avignon 60,000 — then, considering the much larger population of

Constantinople, we might regard 300,000 as not an excessive figure for the total

destruction. For the general mortality throughout the Empire we have no data for

conjecture; but it is interesting to note that a physician who made a careful

study of all the accounts of the Black Death came to the conclusion that,

without exaggeration, Europe (including Russia) lost twenty-five millions of her

inhabitants through that calamity.

At first, relatives and domestics attended to the burial of the

dead, but as the violence of the plague increased this duty was neglected, and

corpses lay forlorn not only in the streets, but even in the houses of notable

men whose servants were sick or dead.

Aware of this, Justinian placed

considerable sums at the disposal of Theodore, one of his private secretaries,

to take measures for the disposal of the dead. Huge pits were dug at Sycae, on

the other side of the Golden Horn, in which the bodies were laid in rows and

tramped down tightly; but the men who were engaged on this work, unable to keep

up with the number of the dying, mounted the towers of the wall of the suburb,

tore off their roofs, and threw the bodies in.

Virtually all the towers were

filled with corpses, and as a result "an evil stench pervaded the city and

distressed the inhabitants still more, and especially whenever the wind blew

fresh from that quarter." It is

particularly noted that members of the Blue and Green parties laid aside their

mutual enmity and co-operated in the labour of burying the dead.

During these months all

work ceased; the artisans abandoned their trades. "Indeed in a city which was

simply abounding in all good things starvation almost absolute was running riot.

Certainly it seemed a difficult and very notable thing to have a sufficiency of

bread or of anything else." All court

functions were discontinued, and no one was to be seen in official dress,

especially when the Emperor fell ill. For he, too, was stricken by the plague,

though the attack did not prove fatal.

Our historian observed the moral effects of the visitation. Men

whose lives had been base and dissolute changed their habits and punctiliously

practised the duties of religion, not from any

real change of heart, but from terror and because they supposed they were to die

immediately. But their conversion to respectability was only transient. When the

pestilence abated and they thought themselves safe they recurred to their old

evil ways of life. It may be confidently asserted, adds the cynical writer, that

the disease selected precisely the worst men and let them go free.

.

J.B. Bury - The History of the Later Roman Empire

(The Plague of Justinian)

Fifteen years later there was a second outbreak of the plague

in Constantinople (spring A.D. 558), but evidently much

less virulent and destructive. It was noticed in the case of this visitation

that females suffered less than males.

|

| Inspired by the Black Death, The Dance of Death, an allegory on the universality of death, is a common painting motif in the late medieval period. |

|

| Bubonic plague victims in a mass grave from 1720-1721 in Martigues, France |

(The Plague of Justinian)

2 comments:

Plague give Empire a blow as they try to rise the ancient lands to their rule .

Reduce a conscription of native citizens , and that weak the core and determination of the army and navy . That bring foreign troops as paid service , what went wrong cause defection and leaving future battle fields.

Matter of concern for strategos .

Those plague weaken the empire , as Justineam keep the same fiscal burden , and public spend ...

That gave way to the war against persia that weaken both empires

Post a Comment