The Death of the Roman Legion

Only 17 years after the battle the Eastern Empire

made its permanent break from Rome.

Sometimes one has to wonder what the point is of border "fortifications".

The Romans spent mountains of money to "secure" their borders on the Rhine and Danube Rivers. But this expensive line of fortifications acted more like a sieve than a wall. For centuries enemies of every kind appeared to pour through in one long endless parade, often with little to no fear of defending Roman armies.

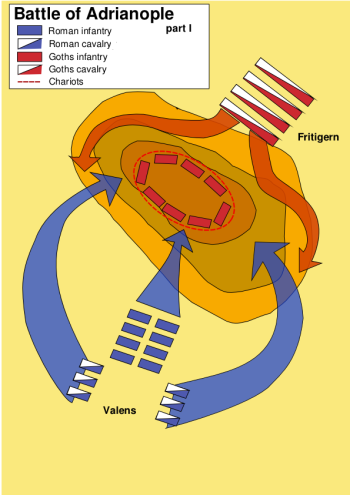

That brings us to the Gothic invasions and the

Battle of Adrianople (9 August 378), sometimes known as the

Battle of Hadrianopolis. The battle

was fought between a Roman army led by the Eastern Roman Emperor Valens and Gothic rebels led by Fritigern.

|

| Eastern Emperor Valens |

The Goth Invasion

The first incursion of the Roman Empire that can be attributed to

Goths is the sack of

Histria in 238. Several such raids followed in subsequent decades, in particular the

Battle of Abrittus in 251, led by Cniva, in which the Roman Emperor Decius was killed.

At the time, there were at least two groups of Goths: the Thervingi and the Greuthungi. Goths were subsequently heavily

recruited into the Roman Army to fight in the Roman-Persian Wars.

Over and over again massive waves of invading peoples pushed into the Empire from beyond the Danube looking for land, wealth and security. . . . usually looking for the wealth of the Romans.

By 376 AD, displaced by the invasions of the Huns, the Goths, led by Alavivus and Fritigern, asked to be allowed to settle in the Roman Empire. Hoping that they would become farmers and soldiers, the Emperor Valens allowed them to establish themselves in the Empire as allies (

foederati).

As the Goths undertook the crossing, Valens's mobile forces were tied down in the east, on the Persian frontier and in Isauria. This meant that only

limitanei units were present to oversee the Goths' settlement. The small number of imperial troops present prevented the Romans from stopping a Danube crossing by a group of Goths and later by Huns and Alans. What started out as a controlled resettlement mushroomed into a massive influx.

The situation grew worse. The Roman generals present began abusing the Visigoths under their charge, they revolted in early 377 and defeated the Roman units in Thrace outside of Marcianople.

After

joining forces with the Ostrogoths and eventually the Huns and Alans, the combined barbarian group marched widely before facing an advance force of imperial soldiers sent from both east and west. In a

battle at Ad Salices, the Goths were once again victorious, winning free run of Thrace.

By 378, Valens himself was able to march west from his eastern base in Antioch. He withdrew all but a skeletal force — some of them Goths — from the east and moved west, reaching Constantinople by 30 May, 378.

Meanwhile, Valens' councilors, Comes Richomeres, and his generals Frigerid, Sebastian, and

Victor cautioned Valens and tried to persuade him to wait for Gratian's arrival with his victorious legionaries from Gaul, something that Gratian himself strenuously advocated.

What happened next is an example of hubris, the impact of which was to be felt for years to come. Valens, jealous of his nephew Gratian's success, decided he wanted this victory for himself.

Opposing Forces

From ancient times to today all sides have exaggerated the numbers of troops involved. This makes it tricky at best to get proper battle estimates.

Eastern Romans - The once great Legions had at one time numbered about 5,000 men. By this period their full strength was far less, and probably no more than 1,000 or so. Most operations were small in scale, and even emperors often led armies numbering no more than a few thousand men.

The fourth-century Roman army specialized in low-level warfare. Pitched battles were rare. They fought instead mainly as the barbarians fought, using speed, surprise attacks, and ambush. Roman troops proved adept at this type of fighting, aided by their training, discipline, clear command structure, and well-organized logistical support.

Valens' army may have included troops from any of

three Roman field armies: the Army of Thrace, based in the eastern Balkans, but which may have sustained heavy losses in 376–377, the 1st Army in the Emperor's Presence, and the 2nd Army in the Emperor's Presence, both based at Constantinople in peacetime but committed to the Persian frontier in 376 and sent west in 377–378.

Valens' army was composed of veterans and men accustomed to war. It comprised seven legions — among which were the

Legio I Maximiana and imperial auxiliaries — of 700 to 1000 men each. The cavalry was composed of mounted archers (

sagittarii) and

Scholae (the imperial guard). However, these did not represent the strong point of the army and would flee on the arrival of the Gothic cavalry.

There were also squadrons of Arab cavalry, but they were more suited to skirmishes than to pitched battle.

The historian Warren Treadgold estimates that, by 395, the Army of Thrace had 24,500 soldiers, while the 1st and 2nd Armies in Emperor's Presence had 21,000 each. However, all three armies include units either formed (several units of

Theodosiani among them) or redeployed (various legions in Thrace) after Adrianople. Moreover, troops were needed to protect Marcianopolis and other threatened cities, so it is unlikely that all three armies fought together.

On the low end of estimates Roman troops in the battle might have been 15,000 men, 10,000 infantry and 5,000 cavalry. The high end might be in 30,000 to 40,000 range.

The Gothic invasion was a

major priority for both the Western and Eastern Empires as both Emperors were bringing armies to the Balkans to beat down the threat.

Under these circumstances the low end estimate of 15,000 is absurd. The Emperor himself would not be marching into a major battle with a small force.

In combining units from the eastern front and the field armies in the Balkans and Constantinople an army of

30,000 to 40,000 men would not be an unreasonable number.

|

These Scandinavian warriors are almost identical with their Gothic relatives because of their unity of culture. The weaponry of the Scandinavians/Vikings was in fact originated from the arms and armor of their Germanic kinsmen in the main European continent , especially from those of the Eastern Teutonic tribes.

(Periklis Deligiannis) |

The Goths - The Gothic armies were mostly infantry with some cavalry, however; in the battle of Adrianople the large force of Gothic cavalry was 5,000 strong.

The Goths and Vandals were predominantly cavalry-oriented armies although, as the Battle of Adrianople illustrates, they could also field redoubtable infantry.

There is little direct evidence for Gothic military equipment. There is more evidence for Vandal, Roman, and West Germanic military equipment, which provides the base for inferences about Gothic military equipment.

Generally speaking there was little difference between well-armed Germanic and Roman soldiers, furthermore many Germanic soldiers served in the Roman forces. The Roman army was better able to equip its soldiers than the Germanic armies.

Late Roman representational evidence, including propaganda monuments, gravestones, tombs, and the Exodus fresco, often shows Late Roman soldiers with one or two spears; one tombstone shows a soldier with five shorter javelins.Archaeological evidence, from Roman burials and Scandinavian bog-deposits, shows similar spearheads.

|

| Goth warriors 4th Century |

Cavalry mainly took the form of heavy, close combat cavalry backed up by light scouts and horse archers. For a Gothic or Vandal nobleman the most common form of armour was a mail shirt, often reaching down to the knees, and an iron or steel helmet, often in a Roman Ridge helm style. Some of the wealthiest warriors may have a worn a lamellar cuirass over mail, and

splinted greaves and vambraces on the forearms and forelegs.

Army Size

Numbers are wildly thrown around that range from as low as 12,000 to 100,000 Goth warriors. Both extreme ends are ridiculous.

In no way would a small army of 12,000 Goths be so dangerous that both Emperors would drop everything and rush to the Balkans. The extreme of high numbers of Goths is simply the traditional over counting of an enemy for some domestic political purpose.

There were probably two main Gothic armies south of the Danube. Fritigern led one army, largely recruited from the Therving exiles, while Alatheus and Saphrax led another army, largely recruited from the Greuthung exiles.

Fritigern brought most if not all of his fighters to the battle, and appears to have been the force the Romans first encountered. Alatheus and Saphrax brought most of their cavalry, and possibly some of their infantry, to the battlefield late. These infantry were indicated as being an Alan battalion.

The Barbarian invasions were literally migrations of entire peoples and tribes. This would result in what I call the

de-Latinization of the Balkans as every new wave of invaders replaced the old Roman population. So it is possible that the entire Gothic and related peoples below the Danube could have run up to 100,000.

In a major campaign the Goths would have gathered all possible males of military age to face down the Romans. That might have resulted in a field army or armies totaling perhaps

30,000 warriors or more. Certainly a force of that size would have commanded the attention of both Emperors.

The Battle

The battle took place about 8 miles north of Adrianople in the Roman province of

Thracia. Though fought between the Goths and the Eastern Roman Empire, the battle is often considered the start of the final collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century.

The Western Emperor Gratian had sent much of his army to

Pannonia when the

Lentienses attacked across the Rhine. Gratian recalled his army and defeated the Lentienses near Argentaria (in modern France).

After this campaign, Gratian, with part of his field army, went east by boat; the rest of his field army went east overland. The former group arrived at

Sirmium in Pannonia and at the Camp of Mars (a fort near the

Iron Gates), 400 kilometers from Adrianople, where some Alans attacked them. Gratian's group withdrew to Pannonia shortly thereafter.

|

| Western Emperor Gratian |

Valens left Antioch for Constantinople, and arrived on the 30th of May. He appointed Sebastianus, newly arrived from Italy, to reorganize the Roman armies already in Thrace. Sebastianus picked 2,000 of his legionaries and marched towards Adrianople. They ambushed some small Gothic detachments. Fritigern assembled the Gothic forces at Nicopolis and Beroe to deal with this Roman threat

As at Ad Salices, the tribesmen had

formed their wagons into a large circle with their families and possessions protected within, and the warriors forming a line outside, facing the approaching enemy.

The Romans began to deploy, the head of the column wheeling to the right and marching to where they would take position as the far right flank of the line. Cavalry and light infantry covered the deployment. The Goths began chanting as they tried to encourage themselves and intimidate their enemy. Others lit bush fires in the dry scrub and grass. The wind took the smoke toward the Romans, which was unpleasant, but more important, made it hard for them to see much of the Gothic position. Fritigern was expecting reinforcements, mainly from the Greuthungi (including a strong force of cavalry), and the smoke would conceal their approach.

The Gothic chieftain needed time to let these men arrive, but that does not mean that he was wholly insincere when he sent a delegation to parley with Valens. Fritigern had little to gain and a lot to lose by fighting the emperor. Negotiation was still his aim, although adding more warriors to his force would strengthen his hand.

Valens refused to receive the first delegation, since the men were of low status. However, when the Goths sent a second proposal and asked for a senior Roman to go over to them as a hostage for the safety of their own party, the emperor's staff got as far as choosing a man for the job. Valens may also have been playing for time, for his army was still moving into position, and yet he too would have been willing to end things with negotiation, especially since the Goths were much more numerous than he had expected. A bloodless victory was as prestigious as a battlefield success, and avoided Roman losses.

Whatever the intentions of the leaders, some of their followers proved more aggressive. When two armies were formed up so close to each other, things were bound to be tense.

Suddenly two Roman cavalry units on the right wing launched an attack, without orders. The Goths soon chased them away, but the fighting quickly provoked the rest of the Roman line to attack, and it drove forward, reaching the laager at some points.

Yet not everyone had been in position. The rear of the column was destined to make up the left of the Roman formation, but these men were only just arriving on the field. The rear of a long column is usually the most aggravating place to be on a long march. Soldiers there wait longest when there is any delay, and then must rush to catch up. Hurried on by their officers, these Roman regiments arrived tired and not yet ready for the general advance.

The account by historian

Barry Jacobsen is a good one. He writes that the Gothic position was upon a low hill, behind a barrier of wagons, defending their camp. The Romans deployed in the plain below them. The Roman foot held the center, the cavalry divided on both wings.

Throughout the hot summer day, the Romans stood deployed under the baking sun; while the Fritigern stretched out peace negotiations. No doubt the Gothic leader hesitated to engage in a trial of arms against the elite “Army in the Presence”. Just as importantly, they were stalling for time to allow their cavalry to return; which were away foraging.

Late in the day, a skirmish broke out between the Roman leftwing cavalry and the Goths opposite them. Losing patience, Valens ordered a general attack.

Standing in ranks all day under a blazing sun, wearing helmet, carrying a 12 pound shield, and in some cases wearing metal body armor will sap the strength of the best conditioned soldiers. Pushing uphill, the already tired Roman forces were sluggish. Even so, progress was being made and the wagonberg was overrun in some places when suddenly, returning to the field, the Gothic cavalry fell upon the flanking Roman horse!

In a cavalry fight, impetus and momentum are of the highest importance. One moment the Roman horse had been mere spectators, holding the flanks and watching their infantry assaulting the wagonberg. The next, they were caught “flat-footed”, as

charging Gothic horsemen smashed into their formations! After a brief and desperate struggle, the Roman squadrons gave way, routing from the field.

|

Goth Hill

Looking south over the battlefield from the hill where the Gothic

wagonberg was located. This is the view the Goths would have

had from their camp of Valens’ army deployed on the plain; and

gives a good impression of how difficult a “slog” up this hill,

under fire from Gothic bows and javelins, the tired Roman infantry

would have had that hot sumer afternoon. |

Deprived of their cavalry and the flank protection it afforded, the Roman attack on the wagonberg faltered. Roman soldiers, looking over their shoulders, could see and hear the furious melee on their flanks. And though clouds of choking dust no doubt obscured the details, it must have been apparent that their cavalry was fleeing the field.

The victorious Gothic cavalry now wheeled inward,

attacking the flanks and rear of the Roman infantry. At that moment, the Gothic foot sallied from the camp, attacking the Romans from the front. Valens and his men now found themselves surrounded and assailed from every direction.

Ammianus Marcellinus, himself a soldier, provided a vivid description of what followed:

“Dust rose in such clouds as to hide the sky, which rang with fearful shouts. In consequence it was impossible to see the enemy’s missiles in flight and dodge (them; all found their mark and dealt death on every side. The barbarians poured on in huge columns, trampling down horse and men and crushing our ranks so as to make orderly retreat impossible…

In the blinding, choking dust that covered the battlefield, all cohesion and tactical control was lost. Attacked from all sides, the Roman lines crumbled inward. Reports tell how soldiers were pressed together so closely that many could not raise their arms from their sides.

“In the scene of total confusion, the infantry, worn out by toil and danger, had no strength left to form a plan. Most had their spears shattered in the constant collisions… The ground was so drenched in blood that they slipped and fell… some perished at the hands of their own comrades… The sun, which was high in the sky scorched the Romans, who were weak from hunger, parched with thirst, and weighted down by the burden of their armor. Finally our line gave way under the overpowering pressure of the barbarians, and as a last resort our men took to their heels in general rout.”

Some of the elite units held their ground, making a last stand. Foremost of these were two of the Palatine Legions (elite legions that served in the Emperor’s own field force), the

Lanciarii Seniors and the

Matiarii. The Lanciari were the senior legion of the Roman army, and they showed their quality that day. When all others lost their heads, they kept theirs. Valens took refuge in this island amidst the storm. He ordered the reserves brought up; but though comprised of elite cohorts of Auxilia Palatina, these too had fled the field. The officers sent to fetch them followed suit, deserting their emperor.

Accounts differ as to Valens fate. One tale has him struck dead amidst these stalwart last defenders. Another, though, states that he was struck by a Gothic javelin or arrow; and was carried to a nearby farmhouse. There, his bodyguards held the Goths off for a time; till the house was set afire; killing all but one, who jumped free of the blaze and was taken prisoner (later relating the Emperor’s fate). That Valens’ body was never recovered lends credibility to this account.

The battle ended with the coming of darkness, allowing some survivors to fight their way out. On the battlefield, the Emperor and

the cream of the Eastern Roman Army lay dead.

|

Roman Infantry

The blue clothed soldier with the square shields are the Roman legionaries.

The less heavily armed soldier with the lighter, green, oval shields

in the foreground are non-Roman auxiliary troops; in this

case Batavian infantrymen.

.

The spooky wolf’s head protruding over all at the back of the picture is the

animal skin decoration of the vexillarius, the standard bearer of the unit. |

Aftermath

Some two-thirds of the Roman army died. Ammianus compared the disaster to the battle of Cannae in August 216 bc, a devastating battle in which Hannibal had slaughtered some 50,000 Roman and Italian soldiers and captured another 20,000. Valens's force was smaller and very different from the citizen volunteers who had marched to battle the Carthaginians. Nonetheless, Adrianople was a dreadful Roman defeat.

Thirty-five Roman tribunes—officers elected by the people who commanded regiments or were staff officers—also died in the battle. It is possible that they suffered a higher rate of loss than the two-thirds casualties suffered by the rest of the army. Since Valens himself apparently died, casualties among his headquarters may well have been extremely high.

According to the historian Ammianus Marcellinus, a third of the Roman army succeeded in retreating.

The Roman defeat was a great victory for the Goths. Yet strategically, Fritigern and his people had gained very little, for they needed to negotiate with an emperor, not kill one and destroy a Roman army. In victory, the Goths launched an attack on the city of Adrianople, hoping to capture the supplies Valens had brought to support his army, but there were enough soldiers still within the city to easily repulse the Goths. Also, Ammianus refers to a great number of retreating Roman soldiers who had not been let into the city and who fought the besieging Goths below the walls.

Rome's response to its loss at first verged on panic.

Local authorities disarmed and massacred parties of Goths throughout the eastern empire, even some serving loyally in the Roman army. For Gratian, it was more important to ensure a smooth transition of power than to focus on dealing with Fritigern. Early in 379, he appointed a man named Flavius Theodosius as eastern emperor, to replace Valens.

The two men proved able to work together, and the new emperor showed considerable talent as an organizer. He raised new troops, and reinforced the laws against draft dodging. It took time to train the recruits, and so he reverted to the earlier strategy of harassing the Goths whenever possible. After a while, Theodosius grew bolder and attacked a larger concentration. His father had been a distinguished general, but the son proved less talented and the enemy cut up his column.

Still, the Romans won the war slowly and gradually, with no more major battles. Instead, they raided and ambushed isolated groups of Goths, tried to keep control of the important mountain passes and gradually hemmed the migrants into a smaller and smaller area.

They were also keen to accept surrenders. Several groups capitulated to Gratian. He removed them, giving them land in Italy. By the end of 382, all of the Goths within the empire had surrendered.

The Death of the Roman Legion

The long-term implications of the battle of Adrianople have often been debated and re-debated.

One major idea is that the battle represented a turning point in military history, with heavy cavalry triumphing over Roman infantry and ushering in the age of the Medieval knight. This idea is mostly coming from historians who have a Western European knighthood frame of reference, and it is wrong.

Eastern Roman cavalry did not become knights. The cavalry arm of the army simply grew (evolved) because of the mobility of the enemies the Empire faced.

Roman cavalry slowly copied their Persian enemies and became

cataphracts or armored horse archers. The 5th-century

Notitia Dignitatum mentions a specialist unit of clibanarii known as the

Equites Sagittarii Clibanarii - evidently a unit of heavily armored horse archers based on the heavy cavalry of contemporary Persian armies.

The cataphracts were both fearsome and disciplined. Both man and horse were heavily armored, the riders equipped with lances, bows and maces. These troops were slow compared to other cavalry, but their effect on the battlefield, particularly under good generals like Belisarius or the Emperor Nikephoros II, was devastating.

I would say that Adrianople

killed the old style Legion as a primary force in the east. As the older Eastern Legions were destroyed or badly mangled they were not replaced or they merged with new units under new names.

Units did survive Adrianople. For example

Legio I Maximiana is mentioned as still under Thracian command at the beginning of the 5th century, and was in Philae (Egypt, south of Aswan), under the dux Thebaidos.

What was left of Legion units were used more and more to man strongpoints in wars that increasingly became defensive in nature.

Despite a number of reforms, the Legion system did manage to survive the fall of the Western Roman Empire, and was continued in the Eastern Empire until around 7th century. At that time reforms begun by Emperor Heraclius to counter the increasing need for soldiers around the Empire resulted in the

Theme system.

Despite this, the Eastern Roman/Byzantine armies continued to be influenced by the earlier Roman legions, and were maintained with similar level of discipline, strategic prowess, and organization.

(fordham.edu) (Gothic War) (Gothic warfare) (Late Roman army)

(Valens) (Goths) (deadliestblogpage) (militaryhistoryonline)

(historynet) (roman-empire.net) (Adrianople)